History of cage-free

Ruth Harrison was a British animal welfare activist and author. In 1964 she published Animal Machines, in which she describes the intensive poultry and livestock farming. In reaction of this book, the UK government installed a research commission, led by Professor Roger Brambell. The research was into the welfare of intensively farmed animals. The commission formulated recommendation, which became known as Brambell's Five Freedoms, to describe the needs of a animal related to welfare. As a result of the report, the Farm Animal Welfare Advisory Committee was created to monitor the livestock production sector. This lasted in a list with the five freedoms.

This is chapter 1 of our 'Cage Free' booklet

The Five Freedoms have been adopted by professional groups including veterinarians and several organizations.

- Freedom from hunger or thirst by giving access to fresh water and a diet to maintain full health and vigor.

- Freedom from discomfort by providing an appropriate environment including shelter and a comfortable resting area.

- Freedom from pain, injury or disease by prevention or rapid diagnosis and treatment.

- Freedom to express (most) normal behaviour by providing sufficient space, proper facilities and company of the animal's own kind.

- Freedom from fear and distress by ensuring conditions and treatment which avoid mental suffering.

During the period between 1980-2000, there was almost no scientific knowledge about animal welfare available. Animal Welfare mainly focused on fighting against excesses. There were mainly large public campaigns against for example, crates for calves. In the council of Europe, codes of conduct were developed. These codes of conduct only could be adopted by uniformity. This leads to a lot of discussion and a minimum of legislation.

Due to some disease outbreaks like foot and mouth disease, a public debate about intensive farming emerged. In the past farmers produced food, but this production model made a 180 degrees turn. The market no longer dictated the sector. The market became more consumer oriented. Farmers had to produce wat consumers asked for.

In the period from 2010 until nowadays, we focus more on innovation and sustainable products. Food safety, effects on the environment, and animal health are topica that have become very important. Banning outbreaks of salmonella, campylobacter, etc., reduce energy, dust, etc. and reduce the antibiotic use, to prevent antibiotic resistance. New concept were born that have taken these subject and animal welfare into account. For laying hens Vencomatic has the Rondeel concept, where food safety, sustainability, animal health and animal welfare are key. For broilers there is the on farm hatching X-Treck system of Vencomatic.

Due to this development more and more eggs were requested from aviary systems instead of cages. Different non-government groups forced the government to give the birds more freedom. This resulted in a cage ban in 2012 announced by the government in Europe. So, the cage ban in Europe was forced by the government, not by the industry and this had an effect. Since September 2019 in The Netherlands there is also a debeaking ban. We think more countries will follow this example.

The world of keeping laying hens is changing fast. After Europe, other countries are thinking to move or are already moving to animal welfare friendly systems. This process lasted 40 years in the Netherlands, but goes much more rapid all over the world. In the UK, free-range systems are the most popular of the non-cage alternatives, accounting for around 50% of all eggs produced, compared to 4% in barns and 3% organic. But so far most of the layers worldwide are still in cages. Apart from Europa, there is another movement in the cage free direction. American companies, like Starbucks, Mc Donalds, Unilever, public announce that they only want to use cage free eggs in the future. How could this happen? The request for cage free eggs comes from welfare organizations, Non-government organizations, and by large multinational companies. But most important, consumers are moving and the market requests more and more cage free eggs, now and in the future. For example the big company Unilever announces to be fully cage free in 2020 worldwide.

Welfare and cage free

Historically, animal welfare has been defined by the absence of negative states such as disease, hunger and thirst (Bracke and Hopster, 2006). However, a shift in animal welfare science has led to the understanding that good animal welfare cannot be achieved without the experience of positive states (Hemsworth et al., 2015). Unequivocally, the housing environment has significant impacts on animal welfare. Cage and Cage-free housing systems have impact on some of the key welfare issues for layer hens: musculoskeletal health, disease, severe feather pecking, and behavioural expression.

Birds can have bone fragility and muscle weakness when they are unable to move and exercise sufficiently (Webster, 2004). This happens in conventional cages, where birds have extreme behavioural restriction. Therefore, they often suffer from osteoporosis (LayWel, 2006). Of all housing systems, hens in conventional cages suffer the poorest bone strength, and the highest rate of fractures at depopulation (Widowski et al., 2013). In cage-free systems, the hens have the best musculoskeletal health (Rodenburg et al., 2008). A study by Rodenburg et al. (2008) comparing cage-free and furnished cages found that hens in cage-free systems had stronger wing and keel bones than hens in furnished cages. An increased behavioural repertoire and the ability to exercise, including walking, running, perching, wing-flapping, and flying increases musculoskeletal strength, and decreases the incidence of osteoporosis and fractures which occur during depopulation.

Looking at disease, the incidence of bacterial infections, viral diseases, coccidiosis, and red mites in litter-based and free-range systems are higher than in cage systems (Rodenburg et al., 2008; Fossum et al., 2009; Widowski et al., 2013). However, with the correct biosecurity and vaccination programmes, the risk of these incidences will decrease (Martin, 2011; Fraser et al., 2013). Hens in conventional cages may experience metabolic disorders due to lack of exercise. Caged hens can show ‘cage layer fatigue’ which is due to bone weakness, fractures of the thoracic vertebrae, and compression of the spinal cord (Duncan, 2001). Other non-infectious diseases including fatty litter and disuse osteoporosis are more prevalent in conventional cages compared with systems that allow greater opportunities for behavioural expression and movement (Weitzenbürger et al., 2005; Kaufman-Bart, 2009; Lay et al., 2011; Widowski et al., 2013). Fatty liver is a metabolic disease typically seen in conventional cages (EFSA, 2005; Jiang et al., 2014) which can cause rupture of the liver and sudden death. The main factors which are thought to contribute to the development of fatty liver include lack of exercise and restricted locomotion, high environmental temperatures, and a high level of stress (EFSA, 2005).

Feather pecking and cannibalism occurs in all types of housing systems (Bestman et al., 2009). Housing birds in large groups can cause an increased risk of severe feather pecking (Potzsch et al., 2001). However, Management practices that may minimise the risk of severe feather pecking are the provision of adequate nutrition, appropriate feed form, high-fibre diets, suitable litter from an early age onwards, no sudden changes in diet or environmental conditions, minimising stress and fear in the birds, provision of environmental enrichment, appropriate rearing conditions, good husbandry and matching the rearing and laying environments (Kjaer and Bessei, 2013; Rodenburg et al., 2013; Hartcher et al., 2016). Furthermore, feather pecking is heritable (Savory, 1995; Kjaer and Bessei, 2013; Bessei and Kjaer, 2015), and current studies are investigating traits which may predispose particular birds to initiate the behaviour, to enable genetic selection against these traits.

Welfare in cage-free systems is currently highly variable, and needs to be addressed by management practices, genetic selection, further research, and appropriate design and maintenance of the housing environment. Conventional cages lack adequate space for movement, and do not include features to allow behavioural expression. Hens therefore experience extreme behavioural restriction, musculoskeletal weakness and an inability to experience positive affective states. Furnished cages retain the benefits of conventional cages in terms of production efficiency and hygiene, and offer some benefits of cage-free systems in terms of an increased behavioural repertoire, but do not allow full behavioural expression (Hartcher and Jones, 2017). Housing systems for hens differ in the possibilities for hens to show species specific behaviors such as foraging, dust-bathing, perching and building or selecting a suitable nest. If hens cannot perform such high priority behaviour, this may result in significant frustration, or deprivation or injury, which is detrimental to their welfare (Fraser et al., 2013).

Hens should be provided with sufficient space to allow the movements described above to be carried out by each bird taking into account the presence of other birds and the frequencies of exercise and other activities required by the birds to avoid significant frustration, or deprivation or injury. Injurious pecking should be minimized by appropriate housing and management as well as by genetic selection. Wherever possible, this should be achieved by provision for the hens’ needs, including opportunities to avoid birds which carry out the pecking, rather than by beak-trimming. Source: The EFSA Journal (2005) 197, 1-23.

Vencomatic Group and cage free

Vencomatic is a Dutch family based company that has started with nests for hatching egg production in 1983. Hatching eggs are valuable eggs and they need to be handled with care. Nest mat and transition from nest to egg room is very important. From this knowledge of save egg handling, Vencomatic started with traditional nests for layers. We as Vencomatic started with barn egg production around 1984.

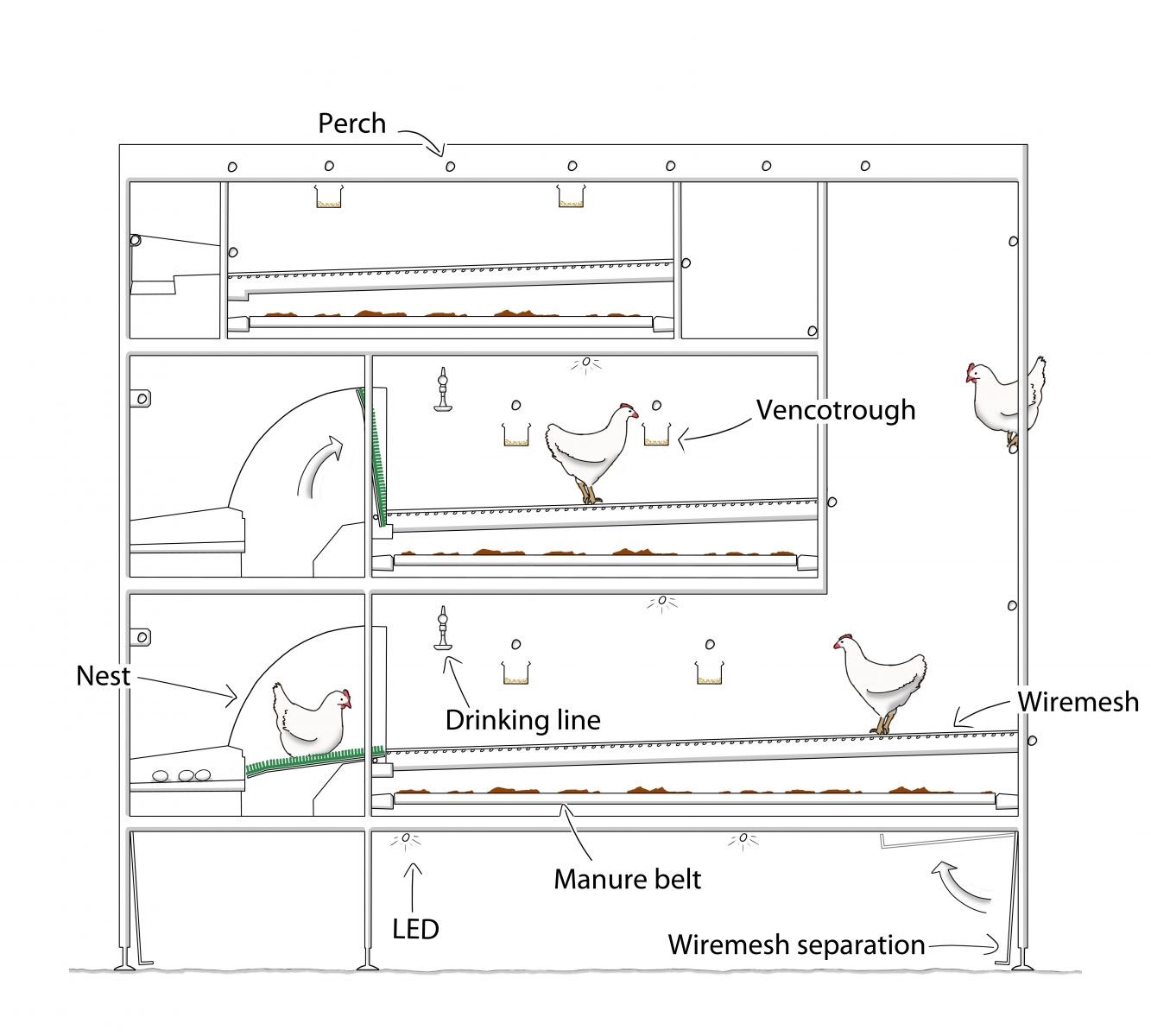

Figure 1. Vencomatic's Bolegg Gallery Aviary system for laying hens.

In Europe the transition to cage free has led breeding companies adapt the birds to aviaries systems. They selected on birds with better performing in aviaries. Also the feed is adapted because the birds have other nutrimental needs. We as Vencomatic have adapted our systems to the needs of the birds (Figure 1). However, a good reared chicken is the key to success in an aviary system. Therefore, Vencomatic also developed rearing systems.

By increasing the amount of birds moving freely in a house, the more challenges their occur. Vencomatic faced these challenges already in the field and overcome the challenges. For example the occurrence of floor or system-eggs. By the lessons we learned in the field Vencomatic developed guidelines for keeping birds in cage free housing, we call this bird management. With good housing systems and bird management techniques in Europe they are capable to house a large amount of cage free birds. The biggest different between cages and cage-free is the management. In cages the farmer controls the birds. In cage free systems, the behaviour of the birds determine the management. You have to look at the needs of your flock and manage them depending in their needs. Our poultry specialists have lots of experience and knowledge with aviary systems and help farmers all over the world with the management of the chickens in our systems to get the best possible results.

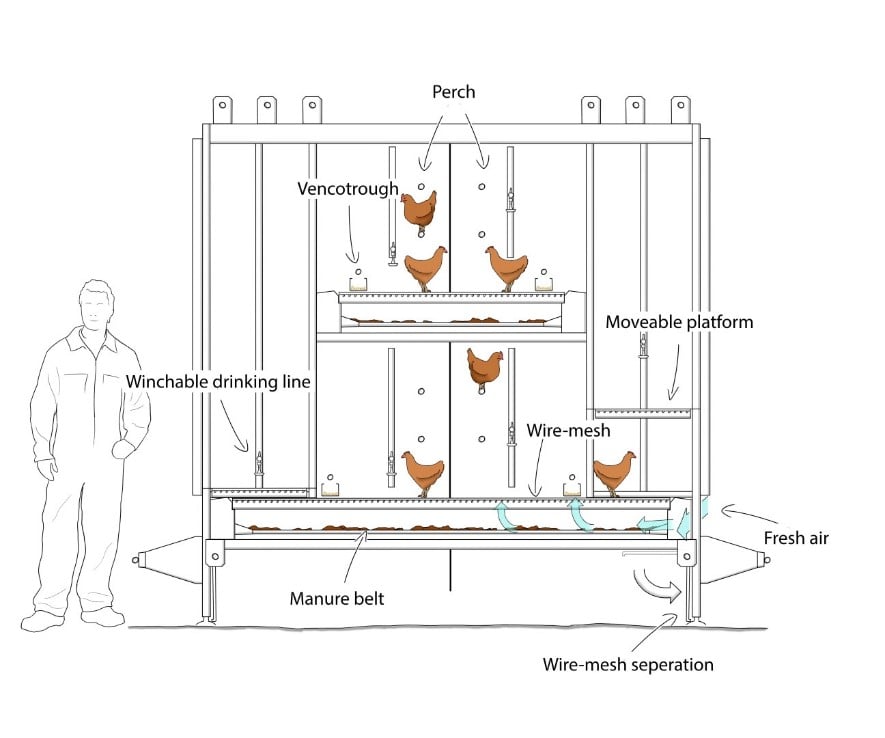

To achieve good results with healthy chickens in a aviary system it is important that you start with a good well trained pullet. A good pullet must be able to: Jump, perch, jump to a perch and roost on perches (Wichman et al., 2009; Freire and Rogers., 2007), sleep away from the litter, respond to light dimming program, search for feed and water on different levels (Figure 2). These ingredients make sure the pullets grow out in strong layers, with strong bones and good developed muscles. In this way, keelbone damage will be minimized but also by strategic positioning off the perches. Rearing in cages doesn’t work when placing them in a production aviary house. For optimal performance, rearing conditions should mimic production conditions (Janczak and Riber (2015).

Figure 2. Vencomatic's Bolegg Starter rearing system for layers.

Due to the tree concept in an aviary system, birds can move easily through the complete system and can express their natural behaviour. This increases animal welfare. They can scratch and dust bath in the litter area, sleep in the system on perches, lay an egg in an safe and dark nest, and eat and drink in the system.. If birds can explore their natural behaviour, you minimize stress related behaviour like feather packing. In an aviary system manure mostly drops on manure belts and will be transported out of the house, this means in the house you have a fresh environment.

It’s no secret that “change is coming.” In fact, change already started. We as Vencomatic has faced this transition in Europe and are now supporting the transition in other parts off the world. Internet is speeding up the public debate and the consumer awareness. The consumer expectations are changing rapidly. Food safety and the reduction of antibiotics is a major issue in the political debate. A positive public image is very important for food processors and retail. Food safety is more and more becoming an important subject for political debates. What took us 35 years, may happen to you within 10 years from now.

With thanks to Ilse Poolen for editing

.png?width=160&height=132&name=Egg%20packers%20-%20Vencomatic%20Group%20(2).png)

.png?width=160&height=132&name=Meggsius%20Select%20-%20Vencomatic%20Group%20(2).png)